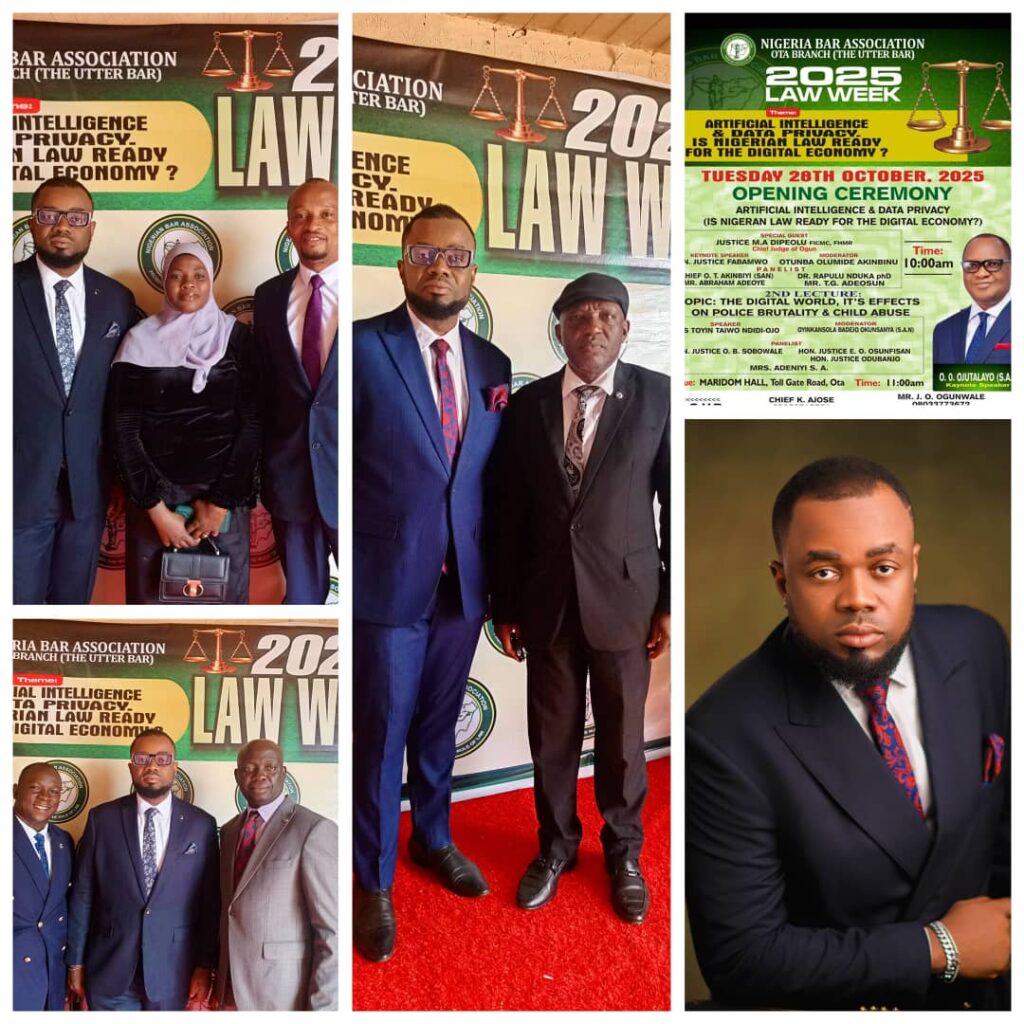

At the 2025 Law Week of the Nigerian Bar Association, Ota Branch, I had the privilege of contributing to the discourse on the theme “Artificial Intelligence and Data Privacy: Is Nigerian Law Ready for the Digital Economy?” My intervention focused on three broad areas: Nigeria’s readiness for the digital economy, the opportunities and risks of artificial intelligence (AI), and the state of data privacy regulation in the country.

From the outset, I made one observation that was difficult to ignore: Nigeria is rarely ready for innovation. Our legal and regulatory responses often trail behind technological realities. The Cybercrime Act is a classic example — enacted long after cybercrime had taken root, and today enforced selectively, with more emphasis on provisions that can silence critics rather than protect critical national information infrastructure.

The Rise of AI and Its Implications for Legal Practice

In today’s digital world, AI and data-driven technologies are reshaping global economies — from commerce to governance, education, security, and even justice delivery. Nigeria is no exception. Our fintech ecosystem, digital identity projects, and e-governance systems are rapidly expanding.

During the session, I highlighted how AI has already begun to influence legal practice in Nigeria. For instance, lawyers are now using AI tools to:

• Automate routine tasks,

• Enhance legal research,

• Draft contracts and pleadings,

• Analyze case trends,

• Predict litigation outcomes, and

• Strengthen client service and practice management.

In my own firm, we use an AI tool to analyze written addresses — it flags strengths and weaknesses and offers strategic insight. This is the new reality of practice.

However, I also emphasized that these advantages must be balanced against significant risks. I referenced a recent case where an Arizona Mother received a call from someone sounding exactly like her daughter, claiming she had been kidnapped — only to discover it was an AI-generated voice clone. This is the dark side of innovation.

We must therefore acknowledge the dangers:

• AI-facilitated deception and fraud,

• Deepfakes and reputational manipulation,

• Algorithmic bias (as seen in the Amazon recruitment example),

• Privacy invasion, and

• The dulling of human cognitive abilities due to excessive dependence on AI.

These issues raise a crucial legal question: Who is liable when AI causes harm — the developer, the deployer, or the user? Nigeria has no answer yet.

Where Nigeria Stands on AI Regulation

One of the most important points I made was this:

Nigeria currently has no AI Act, no dedicated ethical framework, and no legal guidelines on algorithmic accountability, automated decision-making, or transparency.

This is a significant gap at a time when nations are competing not only for economic advantage but also for digital sovereignty. Even the United Kingdom, a more advanced digital economy, relies on broad AI regulatory principles and sector-specific oversight. Nigeria has not taken that initial step.

Data Privacy: Laws Exist, but Implementation Is Weak

On data privacy, I acknowledged that Nigeria has made progress. The Nigeria Data Protection Act (NDPA) 2023 is a strong foundation regulating data processing, protecting individual rights, and setting out obligations for data controllers.

However, our problem is not lack of law — it is lack of enforcement.

I shared a story about an incident that took place when I was the National Publicity Secretary of the Nigerian Bar Association. A foreigner who received NBA emails without subscribing had threatened to take action. I only managed the situation because I understood the gravity — under data protection rules, this is a violation. Similarly, companies still use citizens’ images and personal data without consent. A childhood friend of mine, Chuka, once discovered his family picture displayed on billboards in Lagos — and even Liberia — without approval.

These violations are symptoms of a larger issue: our culture of non-compliance.

Key Gaps in Nigeria’s Digital Landscape

During my presentation, I identified the following critical gaps:

• Absence of AI-specific legislation

• Weak enforcement capacity within the data protection ecosystem

• No clarity on liability for AI-driven decisions

• Data sovereignty concerns due to foreign cloud hosting

• Lack of national AI ethics guidelines

• Low public awareness of digital rights

• Nigeria’s digital progress is policy-driven rather than law-driven, and this is insufficient for the challenges ahead.

Learning from Global Best Practices

I pointed out that other jurisdictions offer useful models:

For example, the EU AI Act adopts a risk-based approach while the UK uses a principles-based and sectoral model.

South Africa is establishing an AI Institute.

I suggested that Nigeria can adapt elements of these systems to create a balanced, locally relevant governance framework.

My Recommendations

I concluded my intervention with a call to action:

1. Enact a Nigerian Artificial Intelligence (Ethics & Governance) Bill to regulate AI deployment, protect citizens, and provide legal clarity.

2. Strengthen the Nigeria Data Protection Commission (NDPC) through increased funding, autonomy, and enforcement powers.

3. Integrate AI and data ethics into legal education to prepare lawyers and judges.

4. Encourage multi-stakeholder collaboration, involving regulators, lawyers, industry, academia, and civil society.

5. Promote regional cooperation within ECOWAS on digital governance.

6. Encourage Nigerian lawyers to explore emerging areas of tech law, describing AI regulation as a “goldmine” requiring expertise.

Conclusion

Nigeria has taken steps toward digital transformation, but our legal architecture remains reactive. To fully secure our future, we must move beyond mere data protection to full-fledged data governance, ensuring that innovation does not erode human rights or national security.

The global economy is already digital. The real question is:

Will Nigeria lead, follow, or remain unprepared?

Dr. Rapulu Nduka

Past National Publicity Secretary,

Nigerian Bar Association